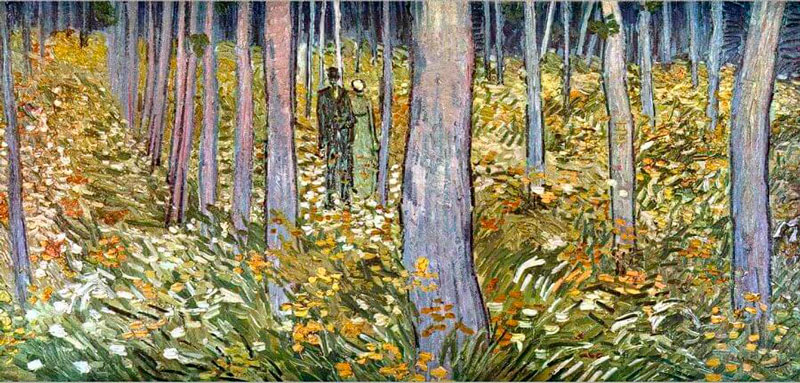

Vincent Van Gogh’s Life

EARLY LIFE

Theodorus van Gogh, a preacher in the Dutch Reformed Church, and Anna Cornelia Carbentus, daughter of a bookseller, marry in 1851. Their son Vincent Willem Van Gogh, the eldest of six children, is born on March 30, 1853, in Zundert, a village in Brabant, in the south of the Netherlands. Four years later, in 1857, Vincent’s favorite brother, Theodorus (Theo), is born.

Read More

Vincent begins his education at the village school in 1861, and subsequently attends two boarding schools. He excels in languages, studying French, English, and German. In March 1868, in the middle of the academic year, he abruptly leaves school and returns to Zundert. He does not resume his formal education.

In July 1869, Vincent starts an apprenticeship at Goupil & Cie, international art dealers with headquarters in Paris. He works in the Hague at a branch gallery established by his uncle Vincent. From the Hague, in August 1872, Vincent begins writing regular letters to Theo. Their correspondence continues for almost 18 years. Theo accepts a position at Goupil’s in January 1873, working in Brussels before transferring to the Hague in November of that year Vincent moves to the London Goupil branch in June 1873. Daily contact with works of art kindles his appreciation of paintings and drawings. In the city’s museums and galleries, he admires the realistic paintings of peasant life by Jean-Francois Millet and Jules Breton. Gradually Vincent loses interest in his work and turns to the Bible. He is transferred in 1874 to Goupil’s Paris branch, where he remains for three months before returning to London. Vincent’s performance at Goupil’s continues to deteriorate. In May 1875 he is sent again to Paris. He attends art exhibitions at the Salon and the Louvre, and decorates his room with art prints by Hague School and Barbizon artists. In late March 1876 Vincent is dismissed from Goupil’s. Driven by a growing desire to help his fellow man, he decides to become a clergyman.

Vincent returns to England in 1876 to teach at a boarding school. In July he is offered a position as a teacher and assistant preacher at Isleworth, near London. On November 4, Van Gogh delivers his first sermon. His interest in evangelical Christianity and ministering to the poor becomes obsessional. On a visit to his parents, Vincent is persuaded not to return to England. Determined to become a minister nonetheless, he moves to Amsterdam in 1877 and attempts to enroll in theology school. When he is refused admittance, Vincent briefly enters a missionary school near Brussels and in December 1878 leaves for the Borinage, a coal-mining district in southern Belgium, to work as a lay preacher. Vincent lives like a pauper among the miners, sleeping on the floor and giving away his belongings. His extreme commitment draws disfavor from the church and he is dismissed, although he continues to evangelize.

THE PRODUCTIVE DECADE

Wrestling with his desire to be useful, in 1880 Vincent decides he can become an artist and still be in God’s service. He writes: “To try to understand the real significance of what the great artists, the serious masters, tell us in their masterpieces, that leads to God; one man wrote or told it in a book; another, in a picture.”

Vincent moves to Brussels and considers enrolling at the art academy, but instead tries to study independently, sometimes in the company of Dutch artist Anthon van Rappard. Because Vincent has no livelihood, Theo, who is at Goupil’s Paris branch, sends him money. He was to do this regularly until the end of Vincent’s life.

Read more

After an argument with his father, Vincent leaves his parents’ house in Etten. Vincent scandalizes his family and Mauve when he takes his model, a pregnant, unmarried prostitute named Sien Hoornik, and her young daughter into his household.

Vincent makes his first independent watercolor and painted studies in the summer of 1882. His uncle Cornelis Van Gogh commissions him to produce 12 views of The Hague.

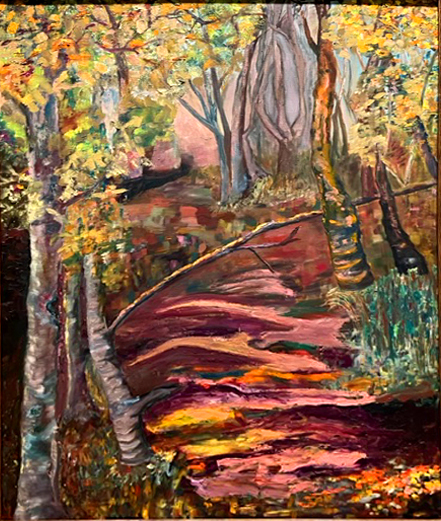

In September 1883 Vincent travels to the province of Drenthe in the northeastern Netherlands. He paints the bleak landscape and peasant workers, but lonely and lacking proper materials, he soon leaves for Nuenen, in Brabant, to live with his parents.

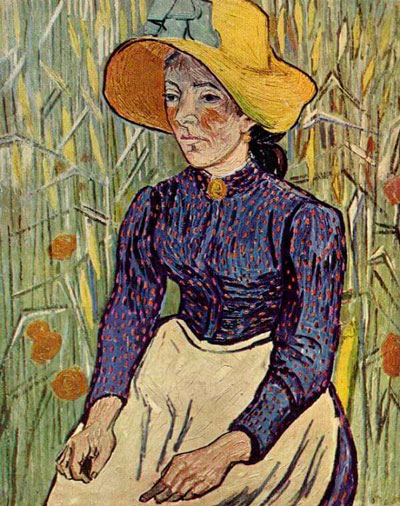

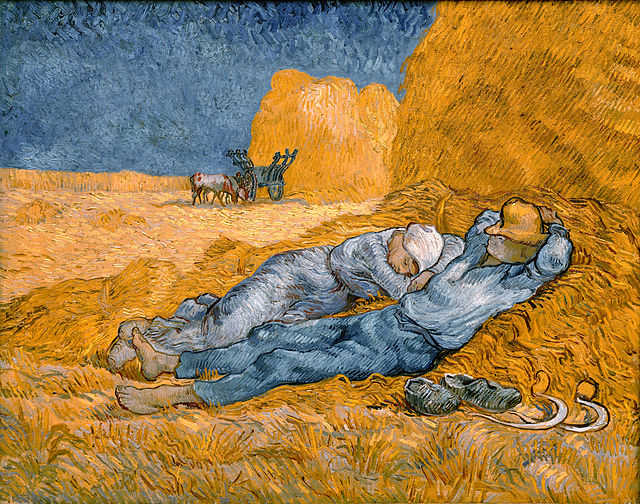

Following in the footsteps of Millet and Breton, by 1884 Vincent resolves to be a painter of peasant life. He sketches and paints the weavers of Nuenen and completes 40 painted studies of peasant heads.

Tensions develop when Vincent accuses Theo of not making a sincere enough effort to sell the paintings Vincent has begun to send him. Theo admonishes Vincent that his darkly colored paintings are not in the current Parisian style, where Impressionist artists are now using a bright palette.

On March 26, 1885, Vincent’s father dies suddenly from a stroke. Shortly afterward, Vincent completes the Potato Eaters, his first large-scale composition and first masterpiece. In part because local clergymen continually thwart his attempts to find models, Vincent leaves the Netherlands for the Belgian city of Antwerp in November 1885. He will never return to his native country. Van Gogh is invigorated by Antwerp’s urbaneness: “I find here the friction of ideas I want.” He has access to better art supplies, the opportunity to draw from nude models, and is exposed to the substantial collections of Dutch and Belgian art in the cities museums and galleries, particularly the paintings of Peter Paul Rubens. Among the exotic goods entering Europe through Antwerp are Japanese woodblock prints, which Vincent begins to collect.

In January 1886 Vincent enrolls in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Antwerp. He grows impatient with the pedantic style of academic training, and within two months he withdraws.

On February 27, 1886, Vincent arrives in Paris. He lives with Theo in Montmartre, an artists’ quarter. The move is formative in the development of his painting style. Theo, who manages the Montmartre branch of Goupil’s (now called Boussod, Valadon & Cie), acquaints Vincent with the works of Claude Monet and other Impressionists. Previously he had known only Dutch painting and the French Realists; now he sees for himself how the Impressionists handle light and color, and treat their original themes from the town and country. For four months Van Gogh studies at the prestigious teaching atelier of Fernand Cormon, and he begins to meet the city’s modern artists, including Paul Gauguin, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Emile Bernard, Camille Pissarro, and John Russell.

Vincent’s Paris work is an effort to assimilate the influences around him. As he begins to formulate his own artistic idiom, he progresses through the styles and subjects of the Impressionists. His palette becomes brighter, his brushwork more broken. Like the Impressionists, Vincent takes his subjects from the city’s cafes and boulevards, and the open countryside along the Seine River.

Through Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, he discovers the stippling technique of Neoimpressionism, also called Pointillism, and freely experiments with the style. “What is required in art nowadays,” he writes, “is something very much alive, very strong in color, very much intensified.”

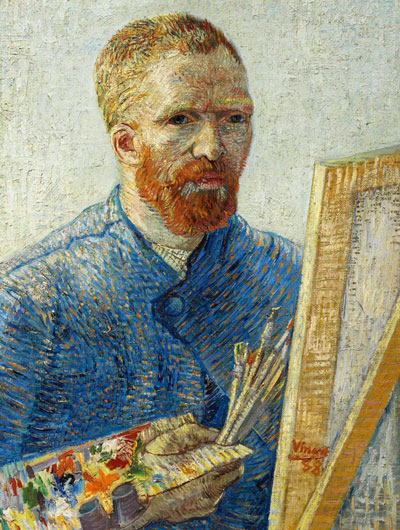

Interested in portraiture as a source of income, but unable to afford models while perfecting his skills, Vincent turns to his own image: “I deliberately bought a good mirror so that if I lacked a model I could work from my own likeness.” He paints at least 20 self-portraits in Paris. The range of his experiments in style and color can be read in the series. The earliest are executed in the grays and browns of his Brabant period; these somber colors soon give way to yellows, reds, greens, and blues, and his brushwork takes on the disconnected stroke of the Impressionists. To his sister he writes: “My intention is to show that a variety of very different portraits can be made of the same person.” One of the last portraits Vincent paints in Paris, Self-Portrait as an Artist, is a dramatic illustration of his personal and artistic identity.

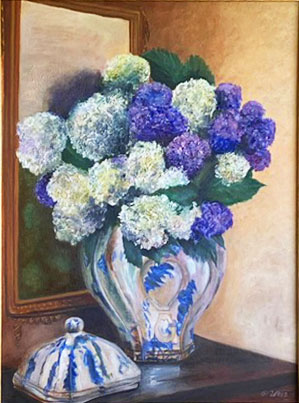

Soon after arriving in Paris, Vincent senses how outmoded his dark-hued palette has become. He paints studies of flowers, which Theo describes as “finger exercises”-practice pieces in which he tries to “render intense color and not a gray harmony.” Vincent keeps balls of wool with threads in different hues-red and orange, blue and yellow, orange and gray-to sample and test the effect of different color combinations. His palette gradually lightens, and his sensitivity to color in the landscape intensifies. Vincent regularly paints outdoors in Asnieres, a village near Paris where the Impressionists often set up their easels. Later, he writes to his sister Wil: “And when I painted the landscape in Asnieres this summer, I saw more colors there than ever before.”

Among his new friends Vincent counts the painters he refers to as the “artists of the Petit Boulevard” — Toulouse- Lautrec, Signac, Bernard, and Louis Anquetin-artists who are younger and not as famous as the Impressionists. Vincent envisions creating a harmonious artistic community in which they will all live and work together. In 1887 he organizes a group show of his and his friends’ paintings at a Paris restaurant. They often gather at Pere Tanguy’s paint shop, where Vincent regularly sees Gauguin. Tanguy, who generously advances supplies to many young artists, occasionally displays Vincent’s paintings in his store window. Vincent buys Japanese prints from the noted art dealer Siegfried Bing and studies them intensively. He arranges an exhibition of Japanese woodcuts at a Paris cafe and makes a few “copies” after Japanese prints. His own work takes on the stylized contours and expressive coloration of his Japanese examples.

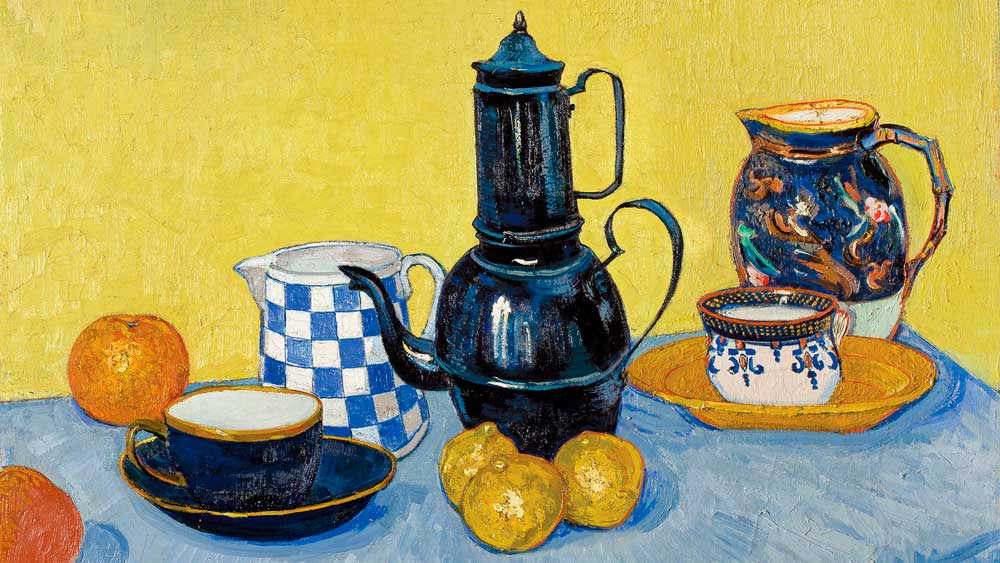

Worn down by his activities in Paris, on February 19, 1888, Vincent leaves for Provence in the south of France: “It appears to me to be almost impossible to work in Paris.” Still hoping to establish an artists’ cooperative, he rents a studio in Arles, the “Yellow House,” and invites Gauguin to join him. In anticipation of his arrival, Vincent paints still lifes of sunflowers to decorate Gauguin’s room. The flowers represent the sun, the dominant feature of the Provencal summer; Gauguin describes the paintings as “completely Vincent.”

Inspired by the bright colors and strong light of Provence, Vincent executes painting after painting in his own powerful language. “I am getting an eye for this kind of country,” he writes to Theo. Whereas in Paris his works covered a broad range of subjects and techniques, the Arles paintings are consistent in approach, fusing painterly drawing with intensely saturated color.

Vincent enters a period of sustained creative activity. He has little to distract him from his painting, for he knows almost no one: “Whole days go by without my speaking a single word to anyone.” He befriends the local postman, Joseph Roulin, and paints portraits of his entire family as well as of his few other acquaintances.

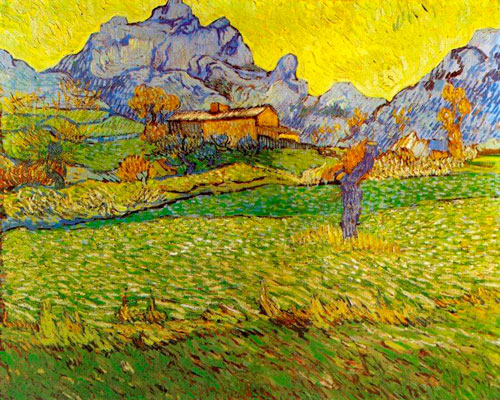

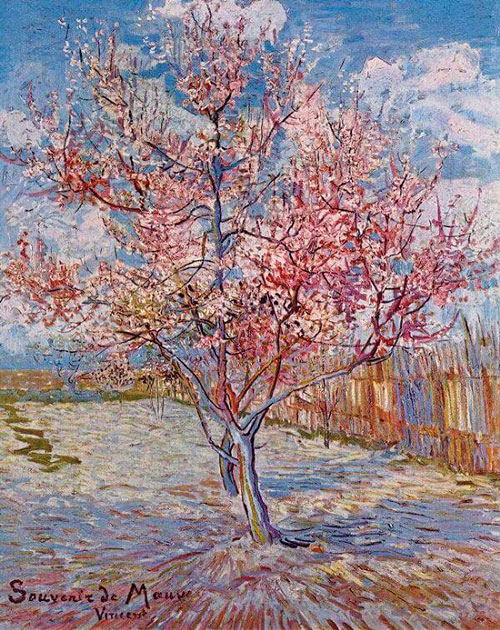

Captivated by the spectacle of spring in Provence, Vincent paints the landscape. He concentrates on blossoming fruit trees and later, in summer, on scenes of rural life. He paints outdoors, often in a single long session: “Working directly on the spot all the time, I tried to grasp what is essential.” He identifies each season and subject with characteristic colors: “The orchards stand for pink and white, the wheatfields for yellow.”

Color also becomes an expressive tool by which Vincent conveys particular emotions, an innovation that aligns his work with Postimpressionism. For Bedroom in Arles, he depicts his room with a stark simplicity, using uniform patches of complimentary orange and blue, yellow and violet, red and green. He writes to Gauguin: “I wanted all these different colors to express a totally restful feeling.” Gauguin finally arrives in Arles in October 1888. For nine weeks he and Vincent work together, painting and discussing art. Gauguin makes a portrait of Vincent in front of one of his sunflower canvases, which Vincent describes as “certainly me, but me gone mad.” Personal tensions grow between the two men. In December Vincent experiences a psychotic episode in which he threatens Gauguin with a razor and later cuts off a piece of his own left ear. He is admitted to a hospital in Arles and remains there through January of 1889.

Theo, in Paris, marries Johanna Bonger in the spring. After his discharge from the hospital in Arles, Vincent is unable to organize his life or set up a new studio. He attributes his breakdown to excessive drink and perhaps tobacco, although he gives up neither. Fearful of a relapse, in May 1889 he voluntarily admits himself to the psychiatric hospital in Saint-Remy, 15 miles from Arles:

“I wish to remain shut up as much for my own peace of mind as for other people’s.” The admitting physician, Dr. Theophile Peyron, notes that Vincent suffers from “acute mania with hallucinations of sight and hearing.

LATER YEARS

Vincent converts an adjacent cell into a studio, and although subject to intermittent attacks, he produces 150 paintings during the year he stays at Saint-Remy. His doctor initially confines him to the immediate asylum grounds, so Vincent paints the world he sees from his room, deleting the bars that obscure his view. In the asylum’s walled garden he paints irises, lilacs, and ivy-covered trees. Later he is allowed to venture farther afield, and he paints the wheatfields, olive groves, and cypress trees of the surrounding countryside. The imposed regimen of asylum life gives Vincent a hard-won stability: “I feel happier here with my work than I could be outside. By staying here a good long time, I shall have learned regular habits and in the long run the result will be more order in my life.

Read More

Relying on his collection of prints, Vincent translates the black and white reproductions into his own intenselv personal color compositions. He makes more than twenty copies of Millet’s peasant scenes, and he reinvents Delacroix’s Pieta, in which the bearded Christ bears some resemblance to himself. After one particularly violent attack, in which he attempts to poison himself by swallowing paint, Vincent is forced for a time to confine himself to drawing.

While in Arles, and Saint-Remy as well, Vincent sends his canvases to Theo in Paris. Despite his illness, he paints one masterwork after another during this time, including Irises, Cypresses, and The Starry Night. Theo praises the new paintings: “They have an intensity of color you have not attained before, but you have gone even further than that. … I see that you have achieved in many of your canvases the quintessence of your thoughts about nature and living beings.”

Others are beginning to notice Vincent’s work, too. The progressive Belgian artists’ group Les Vingt includes six of his paintings in their 1890 exhibition. When Vincent exhibits recent work at the Salon des Indépendants – two canvases in 1889 and ten in 1890 – friends in Paris assure him of their success. “Many artists think your work has been the most striking at the exhibition,” writes Gauguin.

Critic Albert Aurier publishes a favorable review of Vincent’s paintings in January 1890 in which he links the artist to the Symbolists. The Symbolists and other Postimpressionist groups such as The Nabis, had gained critical attention throughout the 1890s for their antirealist artworks. Vincent is moved by Aurier’s article but denies his significance as an artist in a letter to the writer: “For the role attaching to me, or that will be attached to me, will remain, I assure you, of very secondary importance.”

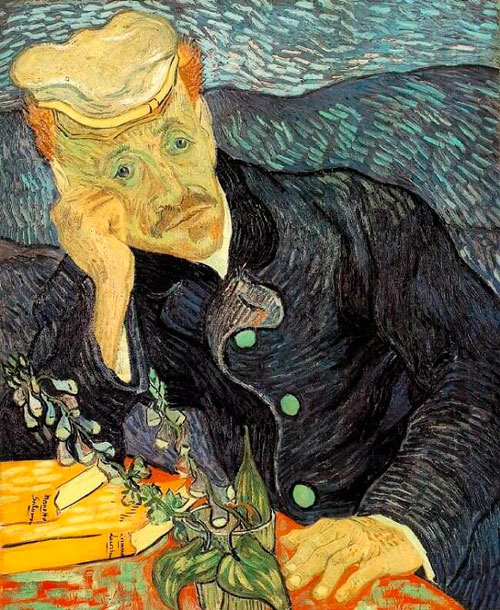

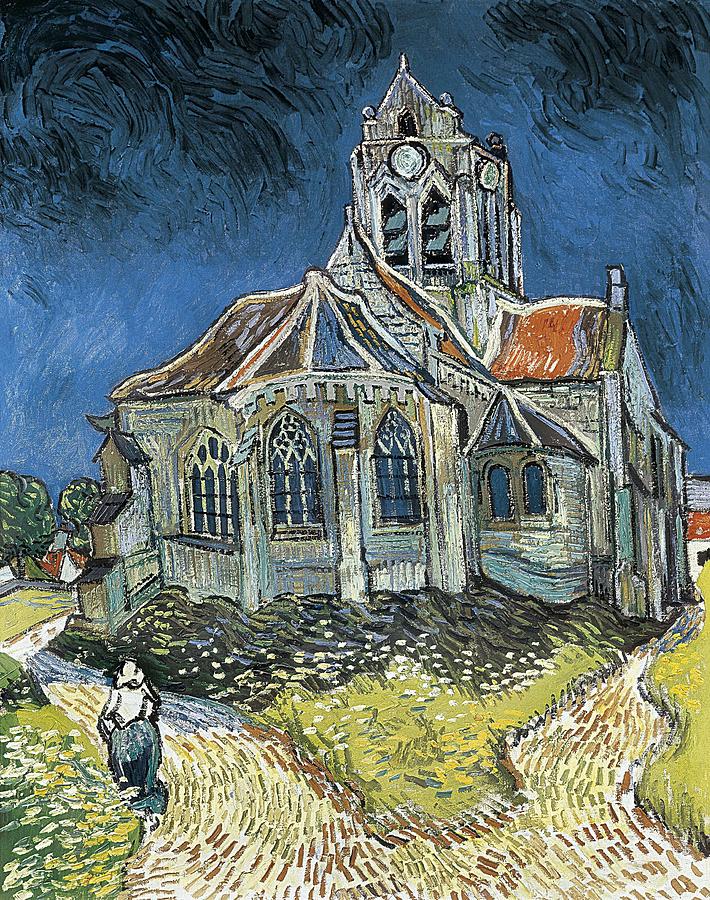

Theo’s son, Vincent Willem Van Gogh, is born in January 1890. Searching for an alternative to his confinement at Saint-Remy, in May 1890 Vincent leaves for Auvers-sur-Oise, near Paris. The location is ideal; he is removed from the immoderate pace of life in Paris, but close enough that he can easily visit Theo. Vincent places himself in the care of Paul Gachet, a homeopathic physician and himself an amateur painter. Vincent warms to Gachet immediately, writing to Theo that he had “Found a perfect friend in Dr. Gachet, something like another brother.” Gachet advises Vincent to put his ailment out of his mind and concentrate entirely on his painting.

Vincent sets about painting portraits of his new acquaintances and the local landscape, including nearby wheatfields and the garden of the painter Daubigny. Working with great intensity, he produces nearly a painting a day over the next two months. A series of 12 canvases in a distinctive panoramic format celebrates country life: “I’m all but certain that in those canvases I have formulated what I cannot express in words, namely how healthy and heartening I find the countryside.” Although he worries that he might again become mentally unstable, Vincent briefly enjoys a peaceful period.

Vincent's passing

In early July Vincent visits Theo in Paris. Frustrated by his work at Boussod’s, Theo is considering setting up his own business, and he warns Vincent that they will all have to tighten their belts.

Strongly affected by Theo’s dissatisfaction, Vincent grows increasingly tense: “My life is also threatened at the very root, and my steps are also wavering.” On July 27, 1890, Vincent walks to a wheatfield and shoots himself in the chest. He stumbles back to his lodging, where he dies two days later, on July 29, with Theo at his side.

Read More

Theo holds a memorial exhibition of Vincent’s paintings in September 1890 in his Paris apartment.

His own health suffers a precipitous decline, and on January 25, 1891, Theo dies. His widow returns to the Netherlands with their infant son and her husband’s legacy, the collection of Vincent’s paintings. After Johanna’s death in 1925 the collection is inherited by her son, Vincent Willem Van Gogh (1890-1978). On the initiative of the Dutch state, which pledges to build a museum devoted to Van Gogh, Vincent Willem Van Gogh, in 1962, transfers the works he owns to the newly formed Vincent Van Gogh Foundation. Construction of the museum building, designed by the modernist Dutch architect Gerrit Rietveld, begins in 1969. The museum officially opens its doors in 1973. Since then, the building houses the largest collection of works by Vincent Van Gogh, on loan from the Vincent Van Gogh Foundation.

Legacy

Largely on the basis of the works of the last three years of his life, van Gogh is generally considered one of the greatest Dutch painters of all time. His work exerted a powerful influence on the development of much modern painting, in particular on the works of the Fauve painters, Chaim Soutine, and the German Expressionists.

Read More

Vincent Van Gogh News

Van Gogh’s insight that will change how you see your everyday life

Brian Schumacher – published on 05/08/23.

In the everyday lives of everyday people Van Gogh saw a latent vivacity begging for expression.

Years ago a friend posed a question I’ve struggled to answer ever since: Why go to an art museum when you can look up the paintings online?

Today, I finally found the answer in the Van Gogh exhibit. It was well composed, and they spared no effort to make the viewer feel fully immersed in the world of Van Gogh. Not only did I feel a tangible connection to the man through seeing the paintings he himself painted, but I was able to better see his brilliant use of color with each individual brush stroke.

That said, I left the exhibit with another question to ponder. Dispersed throughout the paintings were numerous quotes and facts about his life. One which I found to be particularly poignant mentioned Van Gogh’s love for the land and its people, especially those engaged in manual labor. He saw them as individuals “illuminated by … a religiosity that sacralized the humility to daily toil.”

In the everyday lives of everyday people Van Gogh saw a latent vivacity begging for expression. Through his brilliance with a brush he was able to express it in a manner that was both new and lasting.

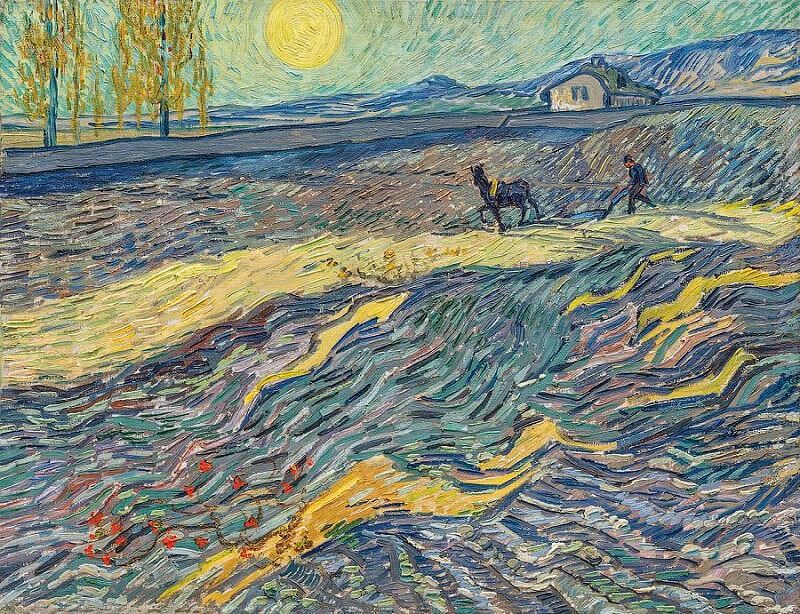

One of these “everyday people” was the Sower with a sack hanging from his shoulder, he cast seeds into the field. The “action” of the painting is simple enough: a man doing his job. But why was I so arrested by this simple action? What was it that fixed my attention to the painting? Certainly I didn’t think it was the most impressive painting — and yet — there I was, staring at it.

It would be fair for one to describe the painting as dreary. The color pallet is drab with its use of blue and gray. Even the sky, which is not cloudy, is also not bright. The only thing I saw, however, was vibrancy. The man is dressed in the colors of the world around him … he doesn’t appear to be working so much as dancing … and though the sky isn’t bright it seems to be cheating toward sunrise.

The man isn’t doing his job, he’s living his vocation, nurtured by the very earth he manipulates. Captured in one moment on canvas is an entire drama played about between man and the cosmos.

Van Gogh was graced with the eyes to see the beautiful in the ordinary. He shared his vision with me personally when I saw that painting in real life and in real time. Because of that interaction I now ask myself frequently what dramas do I see unfold everyday that I merely dismiss as ordinary?

This is Van Gogh’s copy of Millet’s Sower and, Millet’s Sower is a ‘descendant’ Pieter Brugel’s plowmen. Van Gogh’s attachment to the farmers and workers of his day reflects St Vincent de Paul’s influence on the countryside as well as the cities of France and beyond.

Charitable organizations

Tap into Van Gogh’s Spirituality with a Donation!

Support Shadow Box Theatre!

Since 1967, the Shadow Box Theatre has reached over two million children, teachers, and caregivers — and continues to reach over 35,000 happy audience members every year, broadening horizons and reaffirming the values of diversity, tolerance, and self-worth.

Because of your generous help, thousands of inner-city children were able to experience theatre for the first time, and many were able to further their experience while participating in our Theatre Arts Workshops.

The impact of your contribution can be seen in their smiling faces and their educational, cultural, and creative growth. Donate Now! https://shadowboxtheatre.org/support

1% of all Gross Profit from sales with the purchase of Vincent Van Gogh Coffee & Vincent Van Gogh Tea will be donated to this organization.